A multiagency force of federal and state authorities in Brazil dismantled communication towers and illegal cellphone shops, as organized crime embraces technology to further its criminal pursuits.

The operation launched on August 6, raiding several points in territory controlled by Brazil’s most powerful criminal organization, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), in the State of São Paulo.

The authorities were aiming to dismantle the group’s criminal logistics, which increasingly use technology to coordinate drug trafficking, run scams, and evade capture. Among the targets were illicit cellphone shops run by the PCC and communication towers that powered monitoring systems the gang used to intercept messages from São Paulo’s Military Police (Polícia Militar do Estado de São Paulo). Authorities believe the PCC used the intercepted communications to anticipate raids and avoid capture.

With Brazilian society increasingly online, organized crime appears to be following suit. Brazil’s Federal Police (Polícia Federal) believe the PCC and Brazil’s second-largest criminal group, the Red Command (Comando Vermelho – CV), have set up call centers across Brazil to run scams online and by phone. But it is not just the mighty PCC that is switching attention to cyber crime.

With the rise of online banking in Brazil, stealing money can now more easily be done remotely as criminals convince victims to transfer cash or sensitive information by phone or email. This has led to virtual crimes becoming increasingly common in Brazil, even as other types of crime drop.

Danger Grows in the Virtual World, Even as Violent Crime Falls

Most property crimes, such as robbery, and violent crimes, like homicide, have fallen in Brazil, but virtual scams continue to grow unabated, targeting an increasingly digitized society.

Fraud in general has been increasing for years, according to data published in the Brazilian Forum on Public Security’s (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública) latest annual report. Such cases hit nearly 2 million in 2023, up from just over 425,000 in 2018.

And while fraud in general is growing in Brazil, online fraud, including scams like phishing emails that trick people into installing malware to steal their identities, is growing the fastest. It increased by 13.6% between 2022 and 2023. Meanwhile, nearly all forms of property crime mentioned in the report decreased during that period.

A Digitization Pandemic

This trend was likely exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. With people forced inside and many industries – such as banking – moving online, criminals followed their targets.

“The pandemic has accelerated the process of digitalization, the process of digital inclusion, and this has had the consequence of the state and institutions not being able to keep up with crime. Crime doesn’t need to pass laws; crime doesn’t need to create processes, procedures or regulations – crime simply does what it thinks it has to do,” said Fábio Diniz, founder and chairman of Brazil’s National Institute for Combating Cybercrime (Instituto Nacional de Combate ao Cibercrime), in an interview with InSight Crime.

This is especially true with the finance industry and online payment methods, such as Pix. More people have bank accounts and make digital payments in Brazil than any other country in Latin America, according to the World Bank.

After Pix was launched in 2021, gangs began kidnapping victims, and then transferring money from their phones with just a few clicks in the app. These groups would work in teams, with one watching and attacking the victim, while the other monitored the accounts, making sure the transfers went through.

But while Brazil’s massive investment in street policing may be bringing down property crimes, like robbery, criminal groups may be finding virtual fraud a convenient low-cost supplement to their operations.

To commit a robbery, a group may need guns and a getaway vehicle. Once the police are called, officers can start analyzing camera footage, trying to identify the perpetrators and tracing vehicles. In Brazil, violent crimes tend to be punished more harshly, all of which raises the costs of a robbery, explained Diniz.

In contrast, running virtual scams mainly relies on an internet connection. A phone call or email may be enough to convince someone to transfer money, and even if the success rate is small, thousands of people can be targeted quickly. Everyone on the internet is a potential target, and crimes can be executed far away from their victims. Tracing virtual crimes back to their authors is difficult, and as a nonviolent crime, penalties in Brazil are lower.

A police operation in July led to the arrest of 34 alleged members of a cybercrime gang in São Paulo. The criminal group committed a series of online crimes, including fake vehicle auctions, online shopping scams, and stealing social media and WhatsApp accounts. Most of their victims were in the state of Pará, thousands of kilometers to the north.

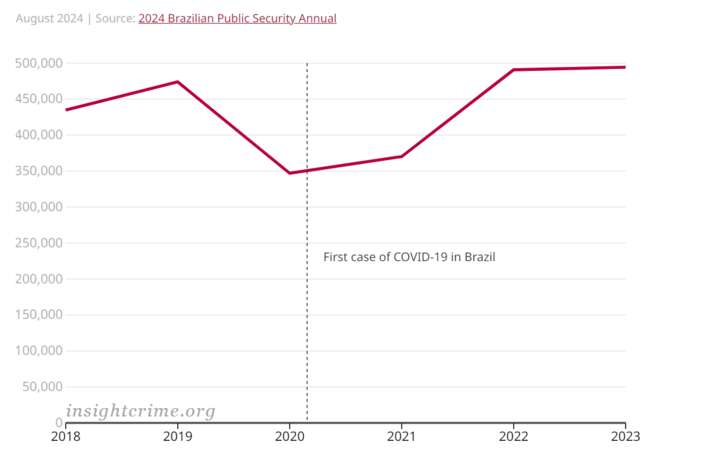

However, the physical and virtual worlds often overlap. For organized crime, smartphones are now an entry point into the virtual criminal world. And while street crime is dropping overall, the demand for phones has caused a rise in nonviolent cellphone thefts. Nationally, the number of cellphones stolen has been increasing year-over-year, rising over 42.5% from 2020 to 2023.

Cellphone thefts in Brazil have taken off following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Cellphones Stolen in Brazil (2018 to 2023)

August 2024 | Source: 2024 Brazilian Public Security Annual

Next Generation of Criminals Emerges Through the Internet

As organized crime finds more opportunities online, tech-savvy teens are joining the digital underworld.

Brazilian police uncovered the operations of a 14-year-old cybercriminal in September 2023. The adolescent is accused of leading a gang that hacked into the government’s official security systems and sold their logins and passwords online. The group used this access to falsify official information and documents from the police, the army, and the justice system.

Aside from forming their own groups, major criminal organizations may be turning to adolescents to enhance their cybercrime operation, according to Samira Bueno, Executive Director of the Brazilian Forum on Public Security. “We’ve noticed that teenagers are working on these [virtual] scams because they are more digitally literate than the crime leaders,” she said in an interview with InSight Crime.

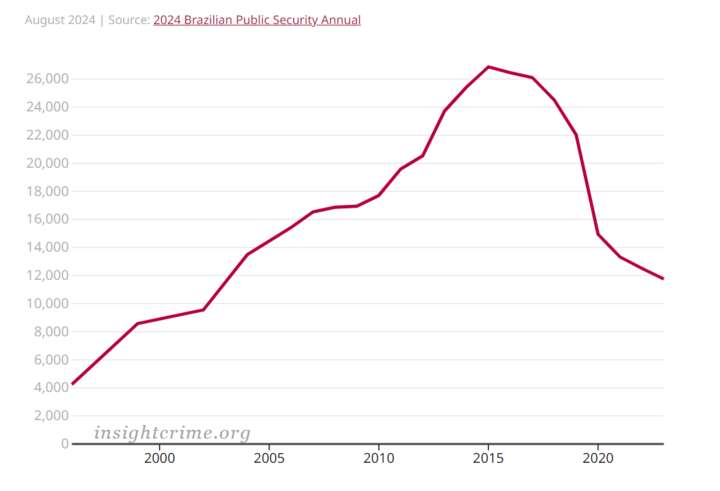

As cybercrime increases, other crimes for this age group seem to be declining. The number of Brazilian adolescents in juvenile detention dropped to around 12,000 in 2023, down 56% from a 2016 peak of almost 27,000.

This is in part due to Brazil’s investment in police on the street, which seems to have led to a decrease in the number of violent robberies carried out by teenagers. However, the drop does not necessarily mean that young people are committing less crime. Instead, it suggests that at least some teens are shifting from the street to online criminal activities, where they are less likely to be caught, Bueno explained.

Juvenile dentention rates have droped as crime rates decline, but teens may be moving to virtual crimes

Adolescents in Juvenile Detention in Brazil (1996 to 2023)

Prison Bars Cannot Stop the Internet

Brazil’s prisons, long hotbeds of organized crime, are now awash with cellphones as criminals run scams while incarcerated.

Technology has made it easier to communicate from anywhere in the world, and increasingly smaller phones are hard to detect. Some prisons in Brazil are known for supposedly having more cellphones than inmates, as prisoners keep up their cybercrime operations behind bars, Bueno explained.

The availability of smartphones means convicts can conduct virtual scams and extort people from inside prison. In a common type of extortion, criminals find the personal information of a victim and contact one of the victim’s relatives outside prison. The scammer claims that the person was kidnapped and demands payment for their release. One investigation against these scams started after a man spent 20 hours on the phone under threats from criminals in October 2023. Authorities struggled to find the perpetrators, who were largely able to hide their digital tracks. But when authorities finally traced the leader of this extortion gang, he was already in prison in Rio de Janeiro.

Smaller groups sometimes use the power and fear of Brazil’s major criminal organizations to pull off their scams. For example, in 2022 prisoners called vendors in the São Paulo metropolitan region claiming to be members of the PCC and demanding payments via Pix to free a PCC leader from jail. The criminals threatened people who refused to pay, and some of the victims transferred the money, believing the callers really were members of the PCC that would harm them and their business if they did not pay.

Authorities in Brazil have discussed the possibility of installing signal blockers in prisons to combat the use of smartphones by detainees. While police officers generally support the adoption of this technology, public prosecutors who focus on criminal networks warn it could hinder their investigations that depend on wiretaps and surveillance inside prisons.

Public prosecutors receive a lot of important information from criminal groups through these mechanisms, which would not work with the blockers. “It turns out that no prison has blockers, except for the maximum security federal prisons”, Bueno said.

Source: Insightcrime