'Exhausted' immune cells in healthy women could be the target for a new preventative breast cancer treatment.

Cambridge University researchers have discovered a new pathway for breast cancer prevention, which involves targeting mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Everyone has BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, but mutations in these genes - which can be inherited - increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

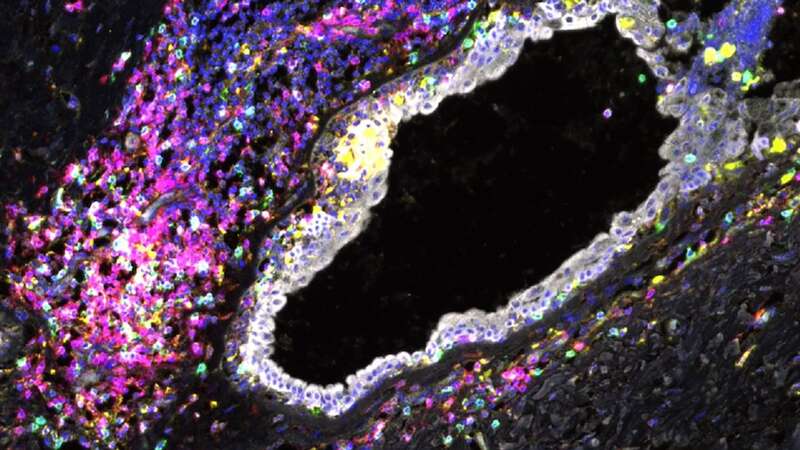

The new study found that the immune cells in breast tissue of healthy women carrying BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations show signs of malfunction known as 'exhaustion'. This suggests that the immune cells can't clear out damaged breast cells, which can eventually develop into breast cancer. This is the first time that 'exhausted' immune cells have been reported in non-cancerous breast tissues at such scale - normally these cells are only found in late-stage tumours.

The results raise the possibility of using existing immunotherapy drugs as early intervention to prevent breast cancer developing, in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations. The team note that this would be a great improvement from current risk-reducing surgery, in which the breasts are removed, which can have a significant effect on body image and sexual relationships.

A famous example of this life changing decision is from actress Angelina Jolie, who had a preventative double mastectomy after she learned that she had inherited the BRCA1 gene from her mother. Other stars who have gone public after mastectomies include Christina Applegate and Sharon Osbourne.

Pregnant Stacey Solomon brands herself an 'old fogy' over NYE plans with Joe

Pregnant Stacey Solomon brands herself an 'old fogy' over NYE plans with Joe

Professor Walid Khaled in the University of Cambridge's Department of Pharmacology said: "Our results suggest that in carriers of BRCA mutations, the immune system is failing to kill off damaged breast cells - which in turn seem to be working to keep these immune cells at bay.

"We're very excited about this discovery, because it opens up potential for a preventative treatment other than surgery for carriers of BRCA breast cancer gene mutations. Drugs already exist that can overcome this block in immune cell function, but so far, they've only been approved for late-stage disease. No-one has really considered using them in a preventative way before."

The study, published in Nature Genetics, used samples of healthy breast tissue collected from 55 women across a range of ages, to catalogue over 800,000 cells - including all the different types of breast cell. Professor Khaled added: "The best way to prevent breast cancer is to really understand how it develops in the first place. Then we can identify these early changes and intervene."

The researchers used a technique called 'single cell RNA-sequencing' to characterise the many different breast cell types and states. Almost all cells in the body have the same set of genes, but only a subset of these are switched on in each cell and these determine the cell's identity and function.

Single cell RNA-sequencing reveals which genes are switched on in individual cells. First author and PhD student Austin Reed said: "We've found that there are multiple breast cell types that change with pregnancy, and with age, and it's the combination of these effects - and others - that drives the overall risk of breast cancer.

"As we collect more of this type of information from samples around the world, we can learn more about how breast cancer develops and the impact of different risk factors - with the aim of improving treatment." The researchers have received a 'Biology to Prevention Award' from Cancer Research UK to trial this preventative approach in mice.

If effective, this will pave the way to a pilot clinical trial in women carrying BRCA gene mutations. The team hope that their findings will help pave the way for an affordable preventative treatment which will be accessible to all women. Dr Sara Pensa from the University of Cambridge's Department of Pharmacology said: "Breast cancer occurs around the world, but social inequalities mean not everyone has access to treatment.

"Prevention is the most cost-effective approach. It not only tackles inequality, which mostly affects low-income countries, but also improves disease outcome in high-income countries."

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus