A series of recent attacks using improvised explosive devices in Mexico points to a generalization of warfare tactics among criminal groups.

This is reported by InSight Crime.

A Mexican Army helicopter was flying over a hill in Apatzingán, in the western state of Michoacán, when it was attacked by a criminal group on January 27. The attackers used guns as well as a drone loaded with an improvised explosive device (IED), according to local media reports.

Days earlier, in the municipality of Río Bravo, on the border with Texas in the United States, a Mexican government vehicle detonated an IED that had been placed on the road, injuring its driver.

The use of IEDs seems to be becoming increasingly common in Mexico. Between 2020 and 2021 only three of these devices were seized, but that figure rocketed to 1,375 in 2022, according to data from the Ministry of National Defense (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional – SEDENA) obtained by InSight Crime.

Since then, the detection of drones has continued to increase. In 2023, the authorities reported 1,681 seizures, and by October 2024, the last month for which data was available, 1,571 had already been counted.

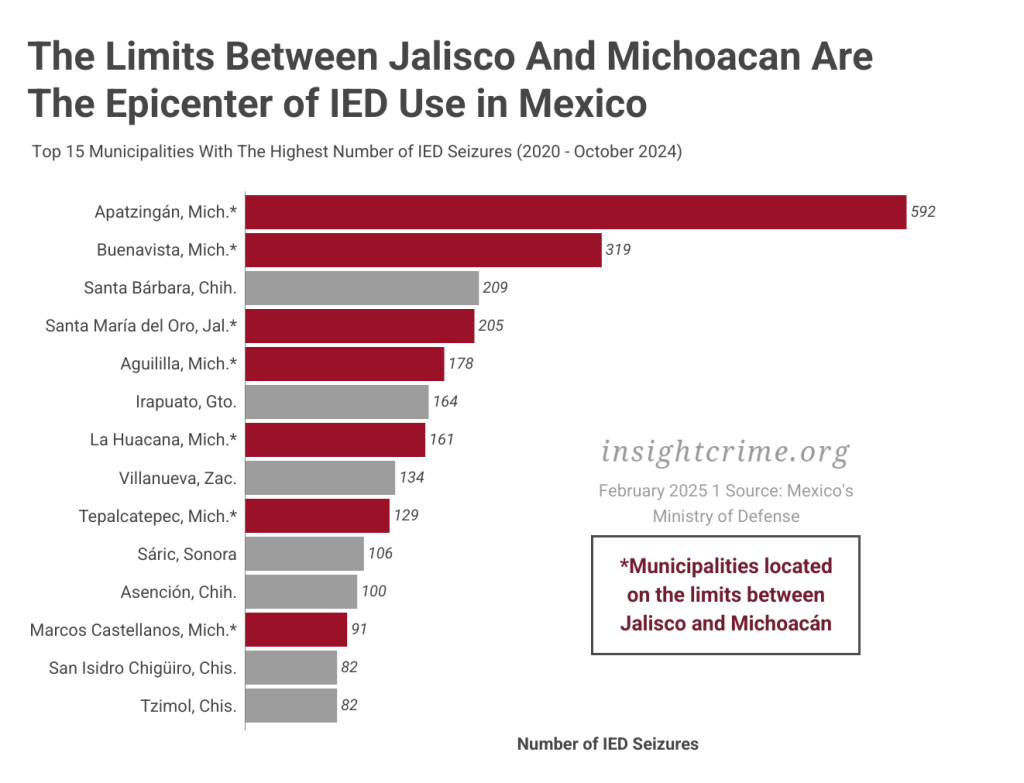

The geographical distribution of the seizures has also spread. Between 2021 and 2022, cases were concentrated in Michoacán, Chihuahua and Guanajuato, states with intense conflicts between criminal groups. And, although they continue to be most common in places marked by violent criminal disputes, by October 2024, the authorities had detected IEDs in 25 of the country’s 32 states.

“IEDs are fully in the cartel arsenals now […] Their use has been going for decades [but] from my perspective it looks like they are far more prevalent now,” Robert Bunker, founder of Small Wars Journal – El Centro, told InSight Crime.

Lower costs, greater access

The increased use of IEDs by criminal groups could be related to how easy they are to make.

Unlike military weaponry, IEDs can be made cheaply and do not require a great deal of technology or complex materials. The first devices seized in Michoacán in 2021, for example, were plastic tubes filled with gunpowder and metal fragments, according to press reports.

Although they have since become more sophisticated, they are still made with accessible materials. For example, recent cases show that plastic tubes have been replaced by metal ones, which can cause greater damage when they explode. In addition, they have been incorporated into landmines and drones to enhance their attack power.

“They are cheap and quick to make. It is much easier to train people to use them [compared to other types of weapon],” Paloma Mendoza, a researcher at the Center for Security, Intelligence and Governance Studies at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico ( Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México – ITAM), told InSight Crime.

For criminal groups, the use of IEDs is strategic and aims to reduce exposure during violent acts. According to Bunker, they are often used to intimidate extortion victims, block roads and hinder the passage of rival groups or state forces, as well as to bomb specific targets, such as enemy hitman camps.

In this sense, Mendoza agrees with Bunker.

“They are part of a war tactic to impose themselves on rivals and protect themselves from state operatives,” said the analyst.

The epicenter

The border area between the states of Michoacán and Jalisco, where Apatzingán is located, accounts for around 40% of all IED seizures in the country.

This is one of the main battle fronts between the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG), and local armed groups resisting its expansion, such as the Knights Templar, the Viagras, remnants of the Familia Michoacana, Cárteles Unidos and self-defense groups.

In Apatzingán, which tops the list of seizures, several properties have been identified that were used as clandestine IED factories. In January, Michoacán’s Ministry of Public Security reported that 60 devices were found in a single house, which were presumed to be intended for use in drones.

The growing use of IEDs has had a significant impact on the local population. According to Julio César Franco, a researcher at the Regional Observatory for Human Security in Apatzingán, they have impeded safe transit for residents, affecting essential activities such as agricultural production, the functioning of schools and the supply of basic products.

“It is part of a climate of violence and criminal practices that have become commonplace in the region. The sense of risk has made us prisoners in our own homes,” he told InSight Crime.

The area has also seen a significant military presence deployed to combat the control of criminal groups, which has led to several armed clashes. Between 2021 and January 2025, the Ministry of National Defense documented 17 IED attacks against soldiers in the region, according to data obtained by InSight Crime.

The CJNG has been the main group to use these devices against the armed forces. In January 2024, for example, an army convoy entered a town in Jalisco that had allegedly been mined by the organization. The explosion killed four soldiers and forced the army to withdraw.

Other local groups have also started to use IEDs to prevent the armed forces from passing through their territories. The Cárteles Unidos group, for example, was allegedly behind an explosion that killed two soldiers and injured another five in the municipality of Cotija in December 2024, according to statements by the Secretary of Defense, Ricardo Trevilla.

Increasing generalization

Although Michoacán and Jalisco account for the majority of IED incidents, other regions are also seeing an increase in their use in criminal conflicts.

In Sinaloa, where a rift has recently emerged between factions of the Sinaloa Cartel, the authorities have begun to seize dozens of explosives and drones. According to local media reports, these have been used both in direct attacks and to destroy the infrastructure of rival groups.

Guerrero, Zacatecas and Sonora have also seen exponential increases in IED seizures in the last two years, according to data from the Ministry of National Defense. These states have been the scene of constant atomizations of criminal groups, which fight for access to drug trafficking, extortion and migrant smuggling.

For Bunker, the increase in criminal competition in Mexico is one of the main reasons for the growing widespread use of IEDs.

“When a plaza is contested by opposing cartels of relatively equal strength, the intensity of the fighting sees their personnel resort to more military-like tactics and weaponry,” he told InSight Crime.

Meanwhile, Mendoza adds that other groups could be imitating this strategy after seeing its effectiveness. A similar dynamic occurred in the 2010s, when several criminal organizations began to replicate the military tactics and extreme violence of the Zetas.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus