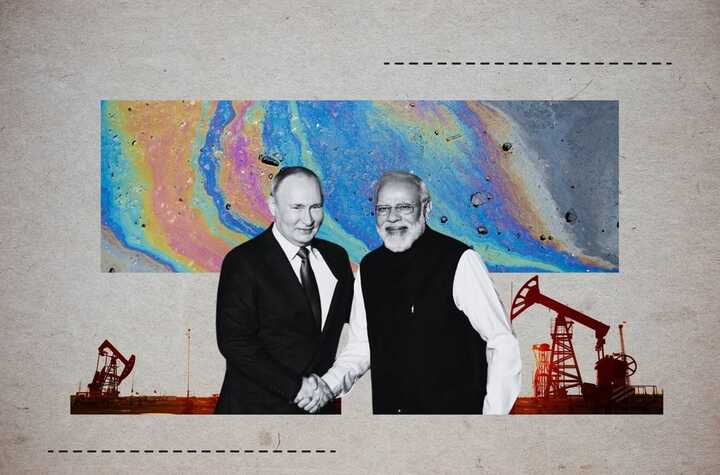

On July 8-9, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was in Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin. New Delhi has formally condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; however, like China, India has been helping Russia circumvent sanctions — in exchange for a huge discount on Russian oil.

Modi’s BJP party did not do well in parliamentary elections this past spring, and his authoritarian tendencies have led to a cooling of relations with the United States. As such, the Indian prime minister needs foreign policy victories if he is to improve his standing at home, and taking up a mediating position between Russia and the West offers one possible opportunity to do so.

Russia is closer than Europe or China

Immediately after his re-election to a third term in June, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi attended the G7 meeting in Italy, where he met with Emmanuel Macron, Joe Biden, and Volodymyr Zelensky. However, Modi has since defiantly ignored the Summit on Peace in Ukraine hosted by Switzerland, limiting India’s presence there to a delegation led by Pavan Kapoor, New Delhi’s ambassador to Russia since 2021. Moreover, Kapoor refrained from signing the final resolution of the summit — explaining the gesture as a signal of India’s neutrality rather than as a challenge to the West. After all, Modi was a welcome guest at the G7 meeting, which was well reflected not only in the Indian but also in the Western media. Western leaders still harbor hopes of pulling India to their side — or at least of preventing New Delhi from getting too cozy with Moscow. This setup has given rise to speculation that European states are seeking to make use of India’s neutrality in hypothetical Ukraine peace talks.

For India, the image of a truce envoy — a “friend of the world,” as the country was referred to at the Swiss summit) — is bringing direct economic benefits in the form of cheap Russian oil. However, this does not mean that India is pursuing friendly relations with all members of the world community. Modi skipped the July 3-4 Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Kazakhstan in favor of his Moscow visit, a jab directed at the summit’s initiator, China, whose relations with India cooled years ago due to border conflicts.

But Modi’s visit to Moscow also sends a message to the West.

A rift with the West

The failure of efforts to “cancel Russia” following the start of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has been well documented. Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited Moscow in 2023, but India’s ties to the West are historically stronger than China’s, prompting New Delhi to quite clearly distance itself from Moscow, at least initially. This makes Modi’s recent visit all the more defiant. Although India has so far refrained from openly denouncing the Russian invasion through UN votes, leading Indian newspapers condemned Russia’s aggression almost from the very start. India also interrupted the tradition of annual India-Russia summits, which took place every October for over 20 years (the first was organized in October 2000 at Vladimir Putin’s initiative). But at the September 2022 SCO summit in Kazakhstan, Modi told Putin that “now is not the time for war,” expressing his solidarity with Western condemnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Recently, India’s diplomatic rhetoric has undergone another shift: instead of demonstratively staying away from Russia in public, India has joined the Kremlin in criticizing the West. The change of tone happened for a reason: the recent strengthening of authoritarianism in India has drawn criticism from Western countries, and New Delhi has been responding increasingly sharply. On June 28, Indian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal openly condemned the U.S. and rejected charges brought against India in the 2023 report of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, which shed light on religious intolerance, oppression of minorities, and illegitimacy of court decisions in India.

Instead of demonstratively staying away from Russia in public, India has joined the Kremlin in criticizing the West

Jaiswal emphasized that the U.S. has a poor understanding of India’s domestic affairs and should not interfere with them. Moreover, the diplomat made counter-accusations, saying that in 2023, members of the Indian diaspora in the United States — more than 3 million people — faced “a range of hate crimes,” which involved racism and vandalism at places of worship.

A recent interview with former Indian Foreign Secretary Kanwal Sibal also captures the country’s message to the West: “If you are not able to manage your relations with Russia, it’s not our problem and that’s no reason for us to reduce our ties with Russia.” In the interview, Sibal harshly criticizes American democratic institutions, which he says do not live up to the standard set by India’s recent successes as “the world’s largest democracy”: its latest parliamentary elections were marked by both the highest overall turnout in the country’s history (about 70%) and the highest turnout of women, and they resulted in Modi’s party unexpectedly losing the majority — an outcome that would be hard to falsify.

Nevertheless, India does not seem prepared to cut ties with the United States, which, along with other Western countries, forms a vast labor market for Indian engineers. India’s mission, as articulated by Modi, is to transform the world through artificial intelligence (India’s motto at the G7 summit was “AI for all”). The World Bank regularly issues loans to train Indian tech professionals, and in 2023 this involved allocating $255.5 million for the development of technical education in India. Moreover, Joe Biden’s cabinet has declared the country a key partner in the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy.

India has always been touchy about Western instructions on what it should and should not do, but recently the criticism has been taken particularly sharply. This also has to do with Modi’s attempts to purge India of its colonial legacy, which in his eyes includes both European colonization and earlier Muslim conquests in the Middle Ages. According to the ruling party, Indian national identity should be associated with Hinduism, a religion they look up to as the nation’s spiritual core. This aspiration even motivated an initiative to rename the country from India to Bharat, its traditional Hindu name. So far, however, the proposal has not been adopted. Nearly 15% of India’s population is Muslim, and they did not support the government’s initiative to pretend that they had nothing to do with the history of the country.

The Modi government also seeks to nationalize the country’s economic model, evidenced in a strengthening of the national currency and a shift to self-sufficiency along the lines of the Swadeshi (lit. “one’s own country”) movement, which emerged in the early 20th century as a protest against the trade in British goods. All of these moves create additional fault lines with the West.

Cheap oil and weapons: what Modi wants from Putin

The rapprochement with New Delhi comes with a price that is easy to calculate. India gets Russian oil at a huge discount and pays for it in rupees, which remain contained within the Indian economy. According to The Hindustan Times, this policy kept $25 billion inside India over the past year.

India gets Russian oil at a huge discount and pays for it in rupees

The year 2023 saw a 40% surge in oil shipments from Russia, according to Times of India. Indian refineries buy Russian crude oil for further processing and sale, mostly to Europe. As per the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry data, the country’s revenues from oil sales to European countries reached a total of $18.4 billion last year. For Russia, however, the outcome is ambiguous: on the one hand, the trade helps circumvent sanctions (trade turnover has increased fivefold, from $13 billion in 2021 to $65 billion by late 2023), while on the other hand, the need to settle in rupees largely outweighs the benefits.

India has been on the rise in recent years in every sense. Having caught up with China in terms of population (1.4 billion), it is experiencing rapid economic growth, with the country’s GDP showing an 8.2% increase in the fiscal year that ended in March 2024. Cheap Russian oil is, of course, highly conducive to this growth. However, the economic successes have not kept the ruling party from losing popularity, which creates an additional incentive for Modi’s international endeavors.

In Moscow, it is possible that the Indian prime minister sought to secure an even bigger discount on oil. The meeting may also have addressed a new trade route: an eastern sea corridor connecting Vladivostok in the Russian Far East and Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu state on the east coast of Hindustan. Modi flew to Vladivostok to discuss the project as early as 2019. This route would simplify logistics, facilitating rapid development of trade between the two countries. In addition, despite its stable security relations with Europe and the United States, India may be seeking to expand its long-standing military ties with Russia as well. In 2021, the two countries signed a ten-year agreement on military-strategic cooperation, regular joint maritime exercises, the exchange of military personnel, and joint technological development. However, Modi and Putin may now be preparing a new agreement, one that would touch on cooperation in logistics and the transfer to India of new technologies already tested in real combat operations in Ukraine. Modi is likely to offer India’s industrial capabilities for the manufacture of Russian military equipment.

Modi is likely to push for Russia to manufacture military equipment in India

In terms of military cooperation, India is also flirting with the U.S. Thus, Modi visited Washington in late June 2023 to sign an agreement to enhance India-US military cooperation and expand a logistics exchange agreement signed in 2016. In particular, this agreement provides for the refueling and repair of the two countries’ warships on each other’s territories. A report on India-US military relations names America as India’s largest trading partner in 2022-2023. Modi’s simultaneous dialogue with Washington and Moscow can hardly be seen as anything other than an attempt to secure for New Delhi the most favorable possible terms by playing the two competing sides off against one another.

There is only one problem for India: in the current circumstances, New Delhi cannot afford to abandon its economic partnership with the West or with the Kremlin; therefore, it cannot swear true allegiance to either side — and both partners are likely aware of this reality. Consequently, India can hardly bank on gaining major concessions, despite Modi’s globetrotting efforts.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus