Preliminary data from Copernicus suggests temperature records were shattered, taking world into ‘uncharted territory’

World temperature records were shattered on Sunday on what may be the hottest day scientists have ever logged, data suggests.

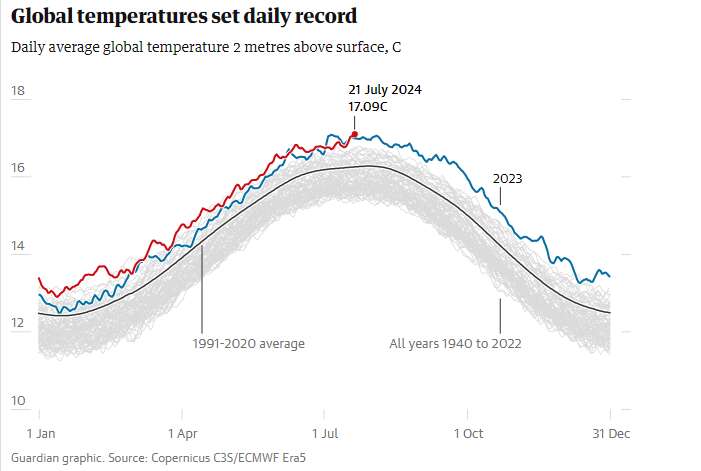

Inflamed by the carbon pollution spewed from burning fossils and farming livestock, the average surface air temperature hit 17.09C (62.76F) on Sunday, according to preliminary data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service, which holds data that stretches back to 1940. The reading inched above the previous record of 17.08C (62.74F) set on 6 July last year, but the scientists cautioned that the difference was not statistically distinguishable.

“What is truly staggering is how large the difference is between the temperature of the last 13 months and the previous temperature records,” said the Copernicus director, Carlo Buontempo. “We are now in truly uncharted territory – and as the climate keeps warming, we are bound to see new records being broken in future months and years.”

The finding comes as large parts of the world roast in punishing heat. Hot weather fuels crackling wildfires that burn homes to a crisp, and triggers silent waves of mass mortality that spill through hospital wards and retirement homes.

Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist who works on the Berkeley Earth data project, said the record was “certainly a worrying sign” on the back of 13 record-setting months and that it should show up in datasets from other research groups. “It also makes it even more likely that 2024 will beat 2023 as the warmest year on record.”

The rapid baking of the planet is expected to slow later this year, at least briefly, if a powerful weather pattern shifts from its neutral state into a cooler phase known as La Niña. But the underlying trend of global heating will persist as long as people pump gases into the atmosphere that act like a greenhouse.

Prof Peter Thorne, director of the Icarus centre at Maynooth University, Ireland, and a coauthor of an IPCC report that found humanity was responsible for all of the observed rise in temperatures since the 1850s, said Sunday’s record might one day be seen as “anomalously cool” if the world did not rapidly reach net zero emissions.

“Just a quick glance at the range of events happening around the globe right now – wildfires, flooding, heatwaves – tells us that we are not remotely prepared for the extremes that this warmer world has bought us,” he said. “We are even less prepared for what is to come.”

A man walks past swamped camper vans on Beveroya in Telemark, Norway, on Monday, after heavy rains in the previous 24 hours. Photograph: Ole Berg-Rusten/EPA

Earlier this month, Copernicus found the world had seared for 12 consecutive months in temperatures 1.5C (2.7F) or more greater than their average before the fossil fuel era.

Though a single year of such heat does not mean world leaders have failed to stop the planet heating by 1.5C by the end of the century – a target that is measured over decades rather than individual years – it pushes more people and ecosystems to the brink.

Global heating has already hit 1.3C and current policies are expected to push it to 2.5C. The difference in suffering is comparable to how the human body reacts to a fever, with small shifts in body temperature that spell the difference between discomfort and death.

“Keeping changes in global average temperatures under 1.5C is not impossible, but it feels like a desperate enterprise,” said Prof Vanesa Castán Broto, an IPCC author who leads a research group on climate urbanism at the University of Sheffield. “Sometimes, it is like waking up buried [under] the ground: pure horror.”

Roadmaps from the IPCC and International Energy Agency (IEA) show that steep cuts in demand for fossil fuels are needed to reach net zero emissions by 2050. A study published last year – which assumed more realistic levels of carbon dioxide removal than previous studies – found that between 2020 and 2050, the supply of coal would have to fall by 99%, oil by 70%, and gas by 84% to hit climate targets.

A person who is buried alive could still try to dig their way out, said Broto. “It may feel hopeless, but you can always take some dirt away.”

When your fingers touch soft ground and break through to fresh air, she said, “this is how we will feel when we know that we have managed to mitigate our emissions, to leave carbon [in] the ground, and to maintain a livable planet”.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus