On the outskirts of Dolores, a small town in northeastern Buenos Aires province, Argentina, several police teams gathered at a gas station on a recent August night to finalize the largest anti-wildlife trafficking operation in the country’s history.

“We had an operational meeting the night before, to avoid the police and brigade vehicles arousing any suspicion,” Emiliano Villegas, head of the wildlife branch of the Environmental Control Brigade (Brigada de Control Ambiental – BCA), a body of specialized agents from the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible – MAyDS), told InSight Crime.

More than 1,000 kilometers to the northwest, in the province of Santiago del Estero, another group of agents were simultaneously getting ready to carry out 13 raids that day in different parts of the country. According to Villegas, 20 vehicles and 70 agents from the BCA and the Federal Police were prepped and ready to go.

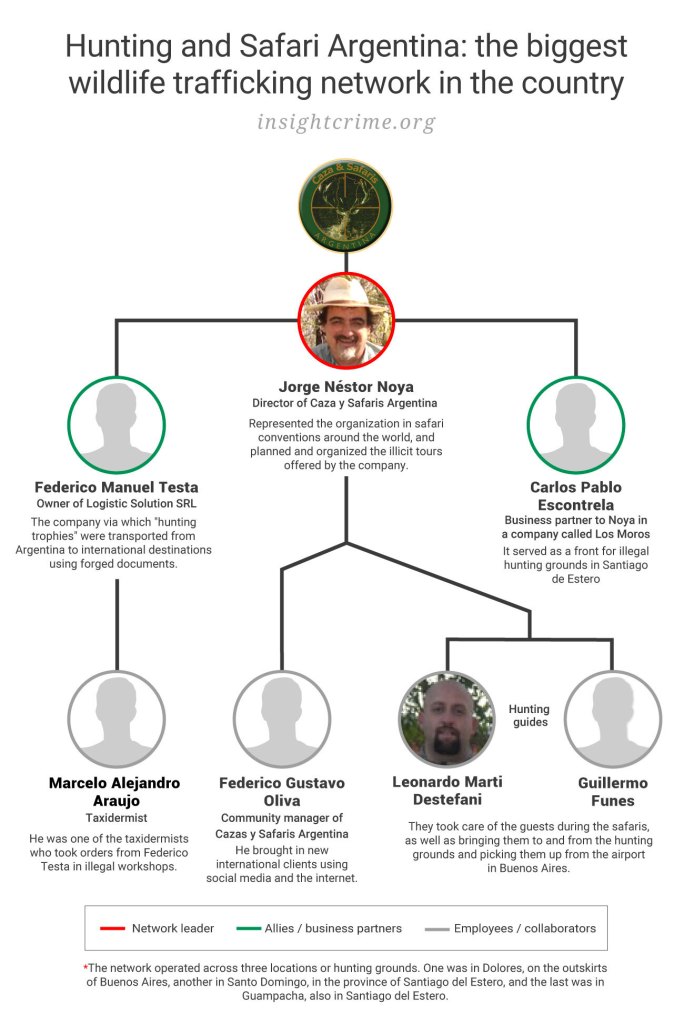

The target of the operation was Caza y Safaris Argentina, a company controlled by Jorge Néstor Noya, a businessman and hunter dedicated to running tourist packages that illegally hunted animals in different parts of Argentina.

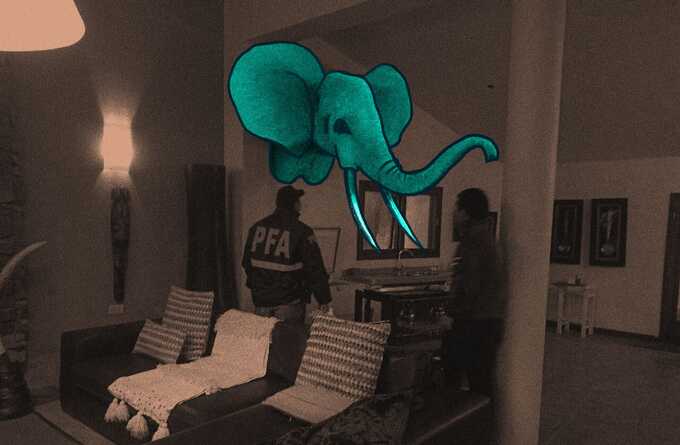

“On the walls of the guest rooms were all kinds of pictures, animal heads, and skulls of protected species. It was a kind of propaganda for the hunters who stayed there,” Villegas said, referring to one of the hunting spots in Dolores.

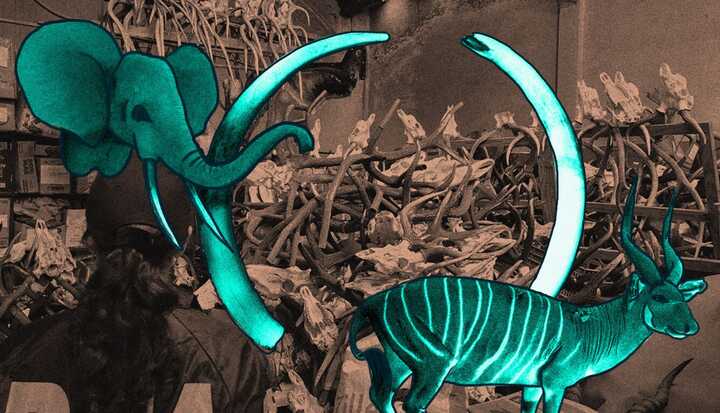

The most exotic trophies were in the bar of the main house, he continued. One of the tables was made from a preserved elephant’s ear, and an umbrella stand had been crafted from one of its legs. Outside the house on the property grounds were all kinds of workshops for preparing hides, skulls, and other animals to be sent to the taxidermist.

“The smell was nauseating. You could smell it as soon as you arrived. I don’t even want to imagine what it was like on summer days,” said Ariana Acevedo, one of the Federal Police agents who carried out the raid.

Patrons of Caza y Safaris Argentina seemed to be completely unaware of the irregularities behind the company, which was a front for one of the largest illegal wildlife businesses in the country. It made hundreds of thousands of dollars of illegal profits for every tour it sold. Prosecutors and police consulted by InSight Crime said this was the first case in the country’s history to link illegal wildlife trafficking to organized crime.

An Old Acquaintance

The organization led by Noya that was dismantled in August 2024 had been on the government’s radar for some time.

In January 2018, a force made up of officials from different divisions of the Federal Police raided one of Noya’s hunting grounds.

Dozens of animals were rescued and several were released, but authorities made no arrests, La Nación reported. Noya was apparently in the US city of Las Vegas at a convention to promote his hunting business and grounds, and his associates were not mentioned either.

The case was shelved until early 2024, when a series of complaints filed by the BCA, and the NGOs Freeland and Red Yaguareté got it reopened. The complaints showed that Caza y Safaris was still operating, Villegas said.

“Freeland’s complaint was the most important as it provided the names of clients that they identified through a facial recognition program,” he said.

“We wrote a report that included the two complaints as well as a news story, which we sent to the environmental crimes division of the Federal Police, so the case got dismissed and reassigned to another prosecutor’s office,” Villegas added.

World Hunting Star

Caza y Safaris operated in plain sight and its director Noya was a celebrity on the international safari scene. But the company managed to avoid authorities’ attention thanks to a strict division of labor, front companies, illegal processes, and the use of social media for promotional purposes, according to prosecutors, the police, and law enforcement sources consulted by InSight Crime.

Noya presented himself as an experienced hunter and veterinarian who had been offering hunting deals since 1979, according to the organization’s website.

He attended shows held by the US organization Safari Club International every year in the United States, and the Expo Cinegetica in Spain, an annual hunting convention, according to case documents accessed by InSight Crime. Noya was in charge of bringing in new clients via these shows. He worked hard on promoting the package deal that included accommodation, meals, drinks, English-language hunting guides, weapons for the hunt, and transportation from the airport in Buenos Aires to potential clients.

Safaris at Just a Click Away

In Dolores, clients could hunt different species of deer, black antelope, water buffalo, wild boar, wild goat, wild pig, mouflon (a species of wild sheep), and capybara, among other animals. In Santiago del Estero clients could go after collared peccaries (a pig-like creature), pumas, deer, turtledoves, ducks, and partridges.

Although some of these species are protected by federal law and international agreements, Caza y Safaris offered year-round hunting packages. Peccaries, for example, are categorized as “threatened” and “endangered” species by Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement that aims to control trade in endangered species worldwide. The hunting of pumas, water buffaloes, capybaras, mouflons, and peccaries is prohibited in Santiago del Estero and Buenos Aires.

Caza y Safaris charged between $900 to $6,000 for each species hunted, according to investigation documents seen by InSight Crime.

“The organization hunted everything that was prohibited and that the deep pockets of the clients could afford,” the Federal Prosecutor’s Office found in a report.

The indiscriminate hunting of these species upsets the balance of the ecosystems where they live, putting their survival at risk and those of the humans around them.

“Ecological balance is like a jigsaw puzzle. If you take a piece out you can’t put it back in. You break it,” said Juan Pablo Arci, assistant prosecutor of the prosecutor’s office in charge of the case.

If they were not lured in by Noya, potential clients of Caza y Safaris came in via his website or social media promotions on Instagram and Facebook.

In addition to hunting, prosecutors discovered that the organization shipped “hunting trophies” such as skulls or preserved animal heads through a man called Federico Manuel Testa, the owner of the company Logistic Solution SRL. Once the species were illegally caught, they were processed in clandestine taxidermy workshops. Noya and his partners falsified documents for these hunting souvenirs and exported them through Logistic Solution, said the prosecutor’s office.

“In reality [the trophies] went out with all the necessary documents. The problem was when they started cross-referencing that data with the hunting permits,” Villegas said.

A man called Carlos Pablo Escontrela, who was a partner in the firm Los Moros S.A., also worked with Noya. According to prosecutors, the firm, which was registered in Santiago del Estero, listed hunting activities as its main function, and served to give the illusion of legality to the hunting services that the organization offered.

The End of Caza y Safaris

Following the operations, Noya, Testa, Funes, and Marcelo Alejandro Araujo were arrested. Federico Gustavo Oliva was captured shortly after, but Leonardo Marti Destefani and Escontrela remain at large, Arci told InSight Crime. More than 3,000 hunting trophies, over 35 firearms, and thousands of rounds of ammunition without the necessary permits were seized during the police sweep in August. Vehicles, additional documents, and related electronic evidence were also confiscated.

This could be the biggest wildlife trafficking case ever brought in Argentina and, as Villegas, Arci, and Acevedo told InSight Crime, it is the first environmental crime case to be linked to organized crime in the country. According to Arci, past environmental crime investigations had never been able to link wildlife crimes to more organized criminal structures.

“Many of the cases we saw involved pets, or illegal trading, but we had never been able to get to the supplier. In this case, we had a network that committed several criminal offenses using an organized structure,” he said.

The case is a milestone in the fight against environmental crimes in Argentina, which are often dismissed as second-class crimes, a trend seen across the region.

But even after this win, there is still much work to be done. Arci hopes the case will send a clear message, not only to criminals but to society at large.

“It is important to build awareness and empathy around these crimes,” said Arci. “More than technical training, we need people to understand that these illegal killings affect us and all future generations.”

Source: insightcrime.org

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus